Pedestrian Design

Most walking takes place on or adjacent to the “public way.” This is the area traditionally set aside in our communities to provide access to private property and to accommodate the movement of people and goods. It is also the area we have come to think of as roadways for motor vehicles. In fact, in many situations the “public way” has been completely consumed by travel lanes for motor vehicles, leaving those who would walk no safe place to do so. Pedestrians are not-and, perhaps, cannot be-prohibited from the public way, but they are given no choice but to walk in the roadway. And the vehicle codes requires them to walk facing traffic when walking in the street, so that they can get out of the way of the cars. The primary intent is not to provide for the safety of the pedestrian, but rather to reinforce that the pedestrian must yield the roadway to the car, even though no other place has been provided for walking. This practice and other anti-pedestrian aspects of street and highway design need to be replaced with a more balanced approach of providing for a range of travel options. We need a commitment to ensure that the use of the public way is planned, designed, and operated in such a way as to provide for reasonable, safe use by all users: motor vehicles, bicycles, and pedestrians. What is needed is good road design.

Rethinking Street Design

Street design involves the design of some of the most important and most used public spaces. This is especially true in the case of residential areas, neighborhood centers, and downtown commercial areas where the design approach must include the various needs of pedestrians, bicyclists, transit, motor vehicles; the street’s relationships to adjacent and future land uses; and where many factors must be compared, considered and decided in order to develop the final design solutions. Children and other nondrivers are too often needlessly impacted by street design that is exclusively motorist-oriented. When a person cannot safely or conveniently travel to without a vehicle, even simple matters such as children’s recreation outside of the home become more rigidly scheduled due to travel coordination needs. By rethinking the design of streets it is possible to accommodate nonmotorist travel and replace some vehicular trips with nonvehicular trips, especially by walking. Scale is a critical street design parameter. What this matter of scale equates to for the designers of streets is a new focus: instead of being primarily concerned with and designing for vehicles and then ‘accommodating’ pedestrians and others, designers must consider the sometimes competing needs and impacts of each design parameter on all of the users of the street. Successful street design in accordance with more pedestrian-friendly principles should result in a larger than usual number of pedestrians in the makeup of the users of the street. However, the pedestrians must obviously share the street with bicyclists, transit vehicles, passenger cars, trucks, and emergency vehicles. All of these users and occupants of the street will require a careful balancing of competing design factors.

Elements of Pedestrian-Friendly Streets

- Streets that are interconnected and small block patterns that provide good opportunities for pedestrian access and mobility.

- Narrower streets, scaled down for pedestrians and less conducive to high motor vehicle speeds.

- Traffic-calming treatments to help ensure that motor vehicles are operated at or below compatible speeds.

- Wide and continuous sidewalks that are fully accessible, that maintain a fairly level cant, and that are well maintained.

- Well-designed intersections to ensure easy, safe crossings by pedestrians of all ages and abilities.

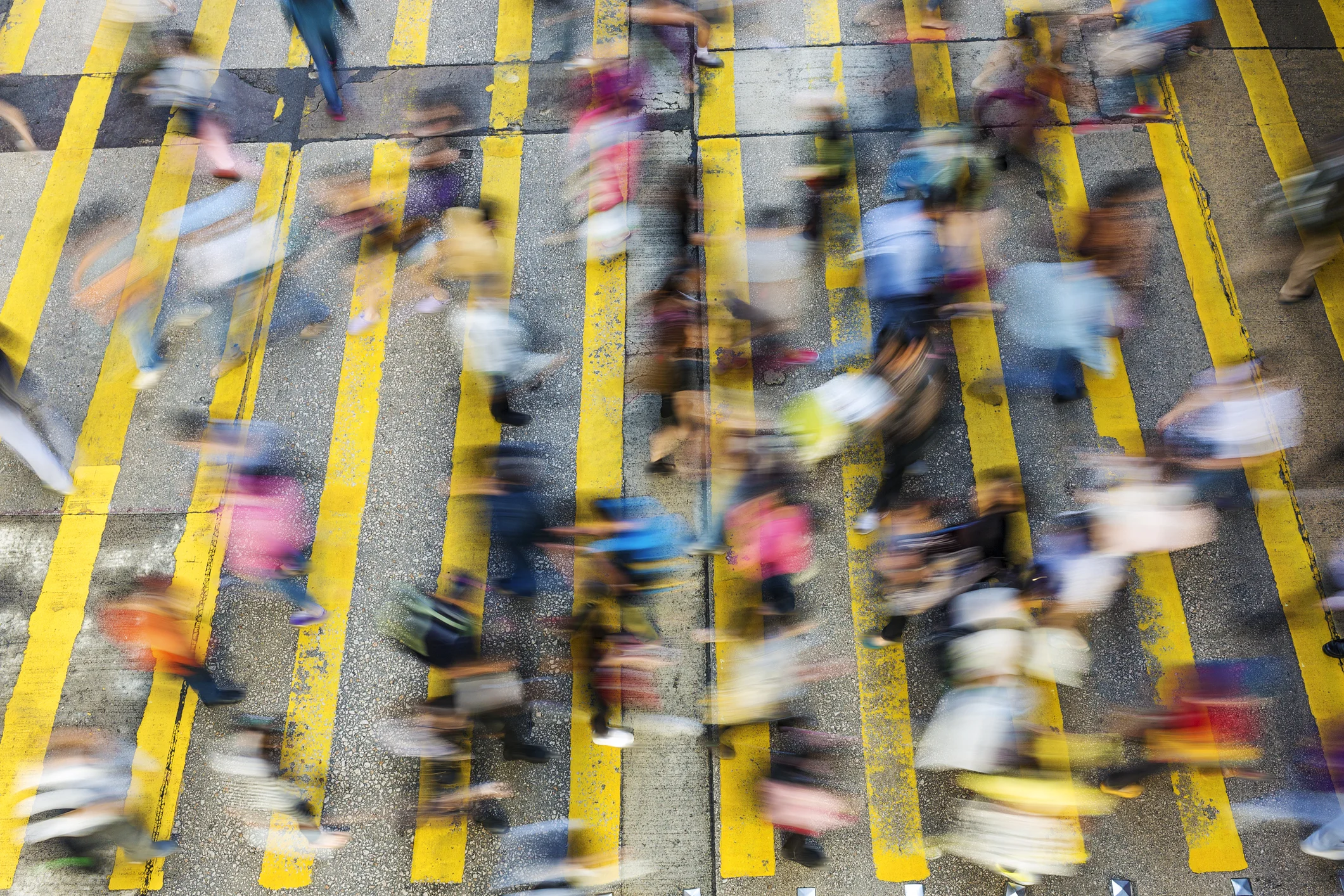

- Well-designed and marked crosswalks, both at intersections and, where needed, at mid-block locations.

- Appropriate use of signs and signals for both pedestrians and motorists, with equitable treatment for pedestrians.

- Median islands on wider streets to provide a refuge area for crossing pedestrians.

- Street lighting designed to pedestrian scale (e.g., shorter light poles and/or lower light fixtures that are designed to be effective in illuminating the pedestrian travel way).

- Planting buffers, with landscaping and street trees that provide shelter and shade without obstructing sight distances.

- Street furnishings and public art intended to enhance the pedestrian experience, such as benches, trash receptacles, drinking fountains, and newspaper stands, placed so as not to interfere with pedestrian travel.

Design Principles

Pedestrians are an integral part of every community’s transportation system. The importance of good pedestrian facility design not only applies to development of new facilities, but also to the improvement and retrofitting of existing facilities for pedestrian use. Research has shown that providing well-designed and maintained pedestrian facilities encourages walking and promotes higher levels of pedestrian travel. Pedestrians want facilities that are safe, attractive, convenient, and easy to use. Unattractive, inadequate, and poorly designed and maintained facilities can be a waste of money and resources and a hindrance to community vitality. Pedestrian needs and facilities should be considered at the inception of all public and private projects and addressed as part of the total design solution. In developing facilities for pedestrians, it is useful to consider a set of guiding design principles that speaks to the needs of pedestrians and the general means by which these needs are to be met. The following design principles represent a set of ideals for every pedestrian improvement. They are listed roughly in terms of relative importance.

- The pedestrian environment should be safe. Sidewalks, walkways, and crossings should be designed and built to be free of hazards and to minimize conflicts with external factors such as noise, vehicular traffic and protruding architectural elements.

- The pedestrian network should be accessible to all. Sidewalks, walkways, and crosswalks should ensure the mobility of all users by accommodating the needs of people regardless of age or ability.

- The pedestrian network should connect to places people want to go. The pedestrian network should provide continuous direct routes and convenient connections between destinations, including homes, schools, shopping areas, public services, recreational opportunities, and transit.

- The pedestrian environment should be easy to use. Sidewalks, walkways, and crossings should be designed so people can easily find a direct route to a destination and minimize delays.

- The pedestrian environment should provide good places. Good design should enhance the look and feel of the pedestrian environment. The pedestrian environment includes open spaces such as plazas, courtyards, and squares, as well as the building facades that give shape to the space of the street. Amenities such as street furniture, banners, art, plantings, and special paving, along with historic elements and cultural references, should promote a sense of place.

- The pedestrian environment should be used for many things. The pedestrian environment should be a place where public activities are encouraged. Commercial activities such as dining, vending, and advertising may be permitted when they do not interfere with safety and accessibility.

- Pedestrian environments should be economical. Pedestrian improvements should be designed to achieve the maximum benefit for their cost, including initial cost and maintenance cost as well as reduced reliance on more expensive modes of transportation. Where possible, improvement in the right-of-way should stimulate, reinforce, and connect with adjacent private improvements